VTH INTERNATIONAL MEETING OF THE SCHOOL

“THE DESIRE FOR PSYCHOANALYSIS”

Presentation of the theme.

Where does the desire for psychoanalysis come from?

With this title, my aim was to reflect on the place of the pass in the School and on the effects of this place. Indeed, pass and School are united but distinct.

Lacan made the pass the end point, and we take it up from him; it is where the desire of the analyst is questioned and, in Lacan’s terms, its aim is to guarantee that there is an analyst. The pass puts in the hot seat colleagues who have the necessarily long experience of analysis, whether as passants or passeurs. There is no obligation to do this and, as Lacan reiterates, it is not for everyone.

The School is different; it is for all its members, even non-practitioners if there are any, and for those who work in institutions and for analysands who come to psychoanalysis without having any idea about where it might lead them. The School concerns them all, for the work the School must undertake is that of psychoanalysis itself in all its aspects, with the aim of causing the desire for psychoanalysis. Certainly, the pass can have effects for all, but on the condition that the discourse about the procedure is not exclusively focussed on the procedure, on what happens or doesn’t happen etc., for then we forget to speak to all the members of the School.

The expression “the desire for psychoanalysis” has produced some surprise and this surprise has surprised me in turn. I am going to argue for it. I understand where the surprise comes from, indeed it was more than surprise, it was a bungled [bévue] reading, due to the fact that in our vocabulary the term we expect is “desire of the analyst”, and as Gabriel Lombardi remarked, the misreading of the title as “the desire of the analyst” occurred repeatedly!

However, the desire for psychoanalysis is not so mysterious; the desire for psychoanalysis designates nothing more than the transference to psychoanalysis, that is fundamental, and aside from affects, a relation to the subject-supposed-to-know of psychoanalysis. Since the latter exists, this transference very generally precedes speaking to an analyst. Not always, it is true; we still sometimes encounter subjects for whom this isn’t the case, notably in institutions, but this is not so common.

Moreover, what do analysts complain of today if not the absence of this preliminary transference, and they deplore the fact that the supposition of knowledge is displaced onto neurobiology and its ideological outcomes above all. And what are we talking about when we say, for example, that Anglo Saxon culture is resistant to analysis, if not just that the transference to analysis is weaker there than in countries where Romance languages are spoken.

Besides, the expression “desire of the analyst” is itself equivocal: in the subjective sense of the “of’, it is the desire that animates the psychoanalyst, the desire that propels someone to assume the function of analyst. In the objective sense, however, it is the desire that there be an analyst. The latter is on the side of the analysand, and we can see it in the form of this particular expectation: the demand for interpretation.

I note again that when Lacan – if we wish to refer to him – introduced the expression “the desire of the analyst” for the first time, he did not make it subjective, he did not designate the desire that animated the analyst. The first time, he used the expression to designate a structural necessity for the transferential relation, the necessity of causing, as desire of the Other, the analysand’s desire that his demand for love covers.

Thus there is a question: where does this desire for psychoanalysis come from?

Let’s look at the history. I would say that Freud generated it ex nihilo. We can draw out the historical conditions, cultural as much as subjective for they depend on the appearance of Freud, and we can also open the chapter on what Lacan formulated about these conditions. But whatever they might be, it is Freud’s saying [dire] that is the cause of the transference to psychoanalysis. It is the “Freud event” that made a desire for psychoanalysis exist. To say “event” is to designate an emergence and a contingency.

Certainly, Lacan succeeded in launching a new transference to psychoanalysis that is clearly evident in the new or revived presence of psychoanalysis wherever in the world his teaching has reached. For him however it was not ex nihilo. And from the start there was a

going beyond the point of arrest in Freudian practice in the so-called “resistance” of the patient and in the final impasse of the refusal of castration.

These two examples suffice to affirm that the desire for psychoanalysis essentially depends on analysts.

Moreover, according to Lacan, transference love is new only because there is “a partner who has the chance to respond”.1 If this partner fails, the transference ends and goes somewhere else. Freud was presented as the partner who responded, while Lacan – and this has always struck me – is introduced as the one who announced he was going to respond anew, at the point where Freud gave up, as did the Post-Freudians too, and he announced it even before the fact. In doing so, he produced in those who listened to him the expectation of his response. In 1973 he says, “this chance” – so good fortune [bon heur] again – “this time it is up to me, this time I have to provide it”.

So the question: how can analysts today continue to have the “the chance to respond?”

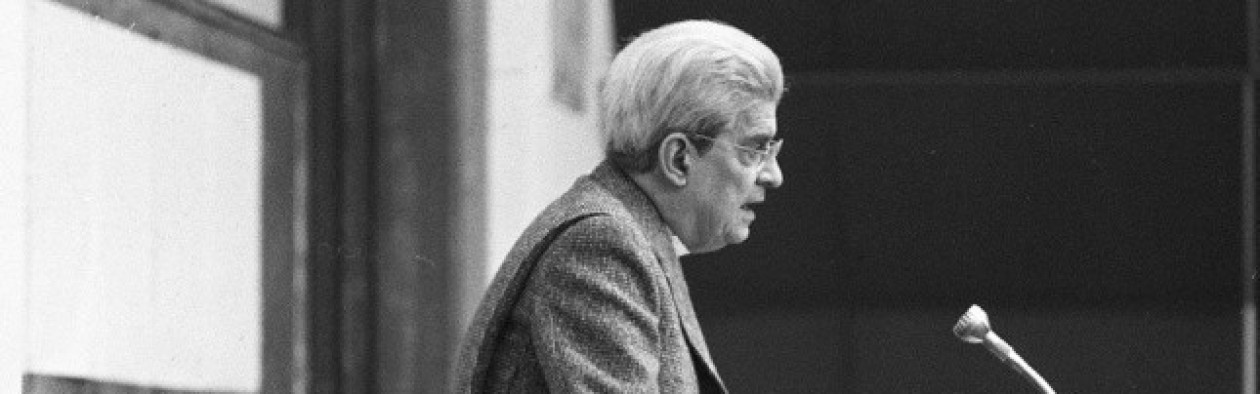

Colette Soler Buenos Aires, April 2015

Translation, Susan Schwartz

First published in Wunsch, International Bulletin of the School of Psychoanalysis of the Forums of the Lacanian Field , Number 15, January 2016.

- Lacan, J. “Introduction à l’édition allemande des Écrits”, Autres écrits, Paris, Seuil, p. 558. ↩